Newton’s science was wrapped together with his various religious interests to such an extent that the two domains cannot really be considered separately. He saw the world as a series of mathematical puzzles set by God for him to solve. He had a strong interest in alchemy, and one of the alchemical beliefs of the period was that the purity of the experimenter affected the result of the experiment. Some have characterised Newton as a devotee of this alchemical path to scientific knowledge – committed to his investigations, and to purity of heart, to the extent that he died a virgin. (Though others have viewed him as a rather mean-spirited character, who got into ugly exchanges with Leibniz and Hooke.) There is no doubt that spirituality in general occupied much of his time, whether Christian theology, or ancient and contemporary alchemy. In fact, Newton was a Christian, an alchemist, and only then a scientist.

As an alchemist he was obsessed with ancient knowledge. He believed that the ancient Egyptians possessed mathematical and astronomical knowledge that was superior to the accomplishments of his day, and believed his own work merely rediscovered these ancient understandings. He also believed that the ancients had knowledge of esoteric matters that went beyond conventional science and mathematics and spent tremendous effort attempting to rediscover these. Many of his biographers have shied away from this, or even tried to cover it over, perhaps embarrassed to discover the deep spiritual life of science’s greatest figure. It is only recently that a fairer appraisal has begun to surface, as scientific opinion has begun to mellow once more to religion, and the enormity and intensity of Newton’s spiritual interests have come to wider awareness.

As a Christian he was unconventional. He was certainly not a Christian merely in order to conform, or to court favour. In fact the branch of Christianity he chose (Arianism) was highly controversial and delayed his career in the early years rather than aiding it. He was a Christian because he found his own somewhat unusual Christian position to be philosophically and scientifically cogent. It was the investigation of Christianity, and not science, or even alchemy, which held his attention until the last years of his life.

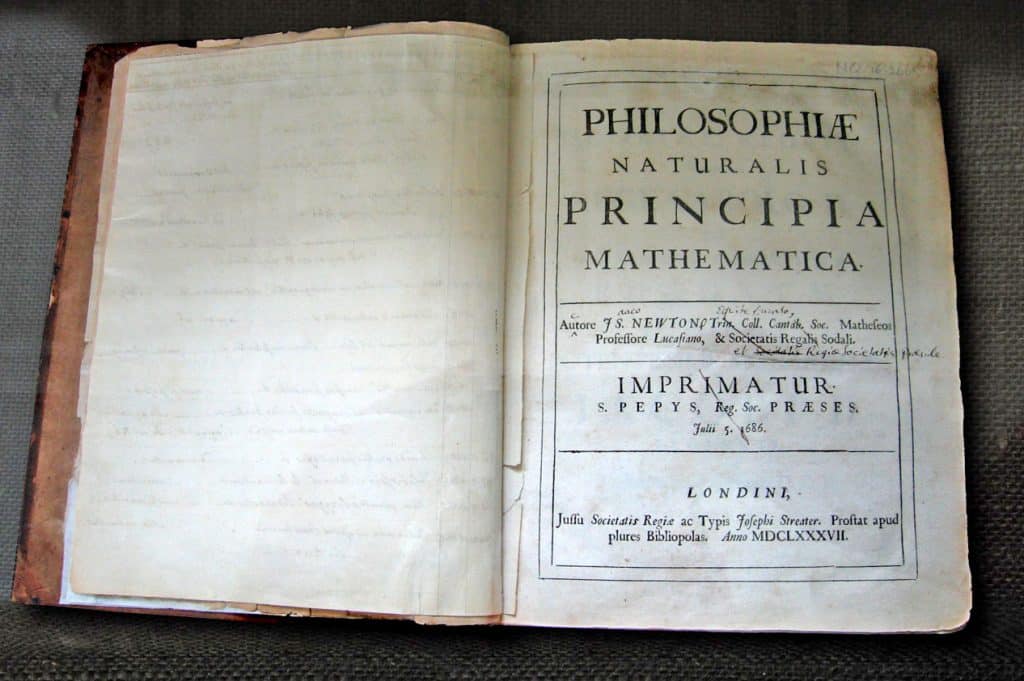

As a scientist he was arguably the greatest ever, and has been voted so in various polls of contemporary scientists. His book, the Principia Mathematica, has been called the greatest scientific feat. By developing new branches of mathematics he was able to think about physics in a way that no one previously had, and one by one revealed the secrets of the motions of objects on earth, of the planets, the oceans, and even the weather. But science was never enough. He remained unsatisfied with science, and spent more effort creating a “theory of everything”, in which science was a part, alongside theology, alchemy, Biblical revelation, and the transformation of the individual soul.

Christianity

Born on Christmas day in the tiny Lincolnshire village of Woolsthorpe-by-Colsterworth, two figures perhaps influenced his intellectual life more than any others. The first was his mother. Newton’s yeoman father died three months before Newton’s birth, uneducated but successful as a manager of agricultural land. This loss led to a difficult relationship with his mother, but it was from her that he derived his interest in Arianism, the framework into which he ultimately attempted to tie all of his scientific and theological study.

The second was a school bully whom Newton resolved to take “vengeance” on. After an altercation with the bully he resolved to beat him in school work and quickly rose to the top of his class. Newton’s life work was to make possible the industrial revolution and subsequently the modern world. In the chain of unintended consequences that makes up the story of history, we have no way of knowing the true significance of the Woolsthorpe-by-Colsterworth school bully in focussing Newton’s mind on the fulfilment of his talents and subsequently shaping the course of global development for the next three hundred years! Nonetheless, within a short time, and while still a youth, Newton had taught himself every known branch of mathematics, and begun to discover new ones.

An understanding of Christianity was the one thing that Newton pursued from the beginning of his life to the end. He eventually tired of the study of both science and alchemy, but he continued to study Christianity and to attempt to unite it with the physics that he had given the world right up to his death. In the case of theology, as with science, Newton was not content to accept convention, but was compelled to investigate matters for himself, to push boundaries, to be original.

The fact that the Christianity he preferred was the unconventional Arianism may have been what prevented him from writing more strongly on the subject of religion in public. He appears to have found Arianism to be intellectually superior, and was loyal to it despite the danger that it posed to his career, and even to his personal safety. The basic difference between conventional Christian theology and Arianism was that Arianism taught that God was superior to Jesus Christ while conventional Christianity taught that they were equal. Newton spent many years creating unpublished theological defences of Arianism, believing it to be the true Christian theological doctrine. He scoured the pages of the Bible for evidence of Arianism and attempted to combine his science and his theological ideas into a single theory, a “theory of everything,” that he had sought in physics and chemistry but failed to find there.

Science

On leaving school Newton initially tried his hand as a farmer, but had no natural love of farming. He gained an assisted placement at the University of Cambridge in 1661 following a recommendation from a local Reverend. Known as a subsizar, this type of placement involved performing servant duties alongside his studies, in place of tuition fees. He was the first in his family to Cambridge. The first to university. The first, on his father’s side, to read or write.

Having completed his studies he returned to Woolsthorpe, and continued to study privately for the next two years. It was here, studying alone in a creaky attic room, that he achieved his major breakthroughs in calculus and gravitation. It is work for which he is regarded to this day as history’s pre-eminent scientific genius.

The laws of the motion of objects which Newton described using equations were to become the cornerstone on which the modern understanding of the world was built. But for Newton they were nothing more than a tangential interest, or a piece in a larger jigsaw. Newton published two major and lasting scientific theories. His theory of gravity – which held centre stage in physics until it was partially supplanted by Einstein’s views on gravity in the early twentieth century, and his theory of light, in which he proposed the modern understanding of light as particles which survived until supplanted by quantum theories of light in the mid-twentieth century – were his two most influential contributions to science. They were summarised in his two classic works, the Principia Mathematica and the Optics.

The most famous, the Principia, unified the work of Galileo and Kepler into a single mathematically coherent and experimentally demonstrated whole which defined the laws of gravity and applied them to describe planetary motion. It was this which made possible the industrial revolution by supplying the laws of mechanics which would lead to 18th century automation. The Principia was a culmination of twenty years of labour, millions of words of notes, and several previous less well-known books.

Investigation of how the physical world worked was merely one aspect of what motivated Newton. He saw everything in the world as a divine secret to be unlocked. In fact science was a relatively small part of a larger spiritual quest. In comparison to alchemy and Christianity, science was the lesser of his concerns. At certain times in his life it also took a back stage to his political and legislative commitments.

Newton on God

The finer points surrounding Arianism aside, Newton’s God aligned strongly with the God of Christian theology and the God of monotheism. Newton gave various descriptions of God in a chapter appended to the second edition of the Principia Mathematica, from which the following quotations are taken:

“from his true dominion it follows that the true God is a Living, Intelligent, and Powerful Being; and, from his other perfections, that he is Supreme or most Perfect. He is Eternal and Infinite, Omnipotent and Omniscient; that is, his duration reaches from Eternity to Eternity, his presence from Infinity to Infinity; he governs all things, and knows all things that are or can be done.”

Newton’s God set the world in motion through an act of creative intelligence: “This most beautiful system of the sun, planets and comets, could only proceed from the counsel and dominion of an intelligent and powerful Being.” Newton’s God “exists necessarily; and by the same necessity he exists always and everywhere.”

Yet this was not deism: God is actively involved in the running of the universe. God has a “propensity towards action,” and God is necessary to keep the universe unfolding moment to moment – a point that Newton discussed at length with Leibniz.

God also intervenes in human events, by providing prophets and prophecy. The evidence of God is in the natural world investigated by the scientist, “we know him only by his most wise and excellent contrivances of things, and final causes.”

God has some of the characteristics of humans, or can be likened to humans by allegory:

“by way of allegory, God is said to see, to speak, to laugh, to love, to hate, to desire, to give and to receive, to rejoice, to be angry, to fight, to frame, to work, to build. For all our notions of God are taken from the ways of mankind, by a certain similitude which, though not perfect, has some likeness, however.”

Yet God is also so very different from us, beyond us:

“as a blind man has no idea of colours, so have we no idea of the manner by which the all-wise God perceives and understands all things.”

Newton’s alchemy

Newton’s alchemical writings were largely reserved for notebooks, a large number of which were destroyed in a fire at his quarters, or were published and distributed under the pseudonym of “Jeova sanctus unus” meaning One Holy God, across secret alchemical societies in London and Europe. Alchemy was considered to be something of an occult art and was treated with suspicion in an age which still feared witchcraft. Nonetheless even the small amount of his alchemical writings that remains is much larger than the full collection of his scientific notes. This itself speaks volumes about the priority of his interests.

In order to appreciate Newton, it is necessary to get a feeling for what alchemy actually was. Most people would describe it as a protoscience, which combined numerology, prophecy, astrology and other occult arts with the beginnings of scientific chemistry and astronomy. While this much was true, alchemy was often much more than this as well. It could be approached as a spiritual path. The internal transformation of the individual was more important that the transformation of physical substances. Purification of body and soul led to the condition of “gnosis,” in which ultimate knowledge of the universe was revealed. What really distinguished alchemy from the 16th century chemistry practiced by brewers, distillers, dye manufacturers, metal workers and other trades people was that the emotional and spiritual state of the experimenter was said to bear on the results of the experiment. Knowledge did not come through hard work or intellectual brilliance alone. It was revealed, by hidden powers, when the alchemist achieved the necessary degree of spiritual purity. The spiritual state of the experimenter was influential on the outcome of the experiment. In this respect alchemy differed markedly from the understanding of the modern scientist.

Alchemists pursued various ends which may seem amusing to the modern audience, such as the manufacture of gold from lead, and it is true that most alchemists were concerned only with the manufacture of gold and with physical riches. Stories, incidentally, abound of alchemists who demonstrated the transmutation of lead into gold through the use of certain elixirs to the astonishment of sceptical overseers; the investigation performed by the previously sceptical philosopher Johann-Friedrich Schweitzer in 1666 is one well-known example.

Regardless of the truth or falsity of any of these claims, the parallel strain of alchemy was entirely spiritually inclined, and this strain understood the gold that the alchemist achieved as spiritual gold. It was this kind of alchemy with which Newton identified. Knowledge of the physical world was part of general rounded development which was ultimately spiritual in nature. The alchemist would eventually achieve the “prima sapientia” – the so called “pristine knowledge” – a spiritual enlightenment in which the soul became utterly pure, and knowledge of all things was given.

It was this quest, and not physics itself, which was the obsession of the most influential physicist in history, for most of his early and middle life.

Later years

Newton lived in permanent pursuit of the divine, believing that science and God were compatible, and could be brought together in a single “theory of everything.” This quest came to increasingly dominate his thinking in later years as he sought to unify his scientific theories of the motions of planets and of light with Christianity.

He had begun this to some extent in his earlier and mainly scientific work the Optics, in which he offered theories on matters such as the Great Flood and the Creation. But these had largely been scientific speculations as to how the science in the rest of the book might have been applied to these events. In his later years Newton changed tack, and attempted to completely synthesise science and religion into a single cohesive theory. This work was by no means completed, and he never attempted to publish these ideas, leaving them only in notebooks to be discovered after his death.

In Arianism, unlike most forms of Christianity, God and Christ were not considered equal. God was superior to Christ, God was the source of all and sustained everything, Christ was one step below this. The difference is rather like the difference between the transcendent God of the theology of Thomas Aquinas, and the so called “demi urge” of Gnosticism – a lesser God which was created by the transcendent God and relied on it for its existence.

Theological opinion at the time was divided as to what extent the resurrected body of Jesus was physical or spiritual. Newton became convinced that the body was spiritual, and cited passages from St Paul in support. It therefore became natural to think of Christ as standing somewhere between the physical universe and God, and this fitted with Arianism. Christ was the first emanation of God. Christ depended on God for existence, but gave existence to everything else. Newton came to think of Christ as the ether; the spiritual body of Christ was the backdrop of the universe in which all physical things arose. He used the spiritual body of Christ to address unanswered questions in his theory of gravitation.

Christ or the ether was the medium through which the action of one body on another at a distance was possible. Hence Newton philosophically drew together his scientific work and his understanding of Christianity. The theory also allowed for the personal nature of Christ – available to each of us at each moment in line with Christian theology – as Christ was literally located throughout the whole of space and time. Likewise the incarnation and resurrection were neatly (and somewhat alchemically) explained as the transmutation of a spiritual into a physical body and vice versa.

Without getting too deeply into theological issues, we can see that Newton was committed to spiritual investigation to the end of his life. The basis of his religion was not merely “faith alone” – he did not believe in God simply because this was the norm for people of his time as certain atheistic scholars in the present age have led us to believe – he believed that a theological understanding of the world was compatible with the science he had given the world, and went to lengths to unify the two. He sought, effectively, the kind of “theory of everything” that transpersonal and integral philosophers are still searching for today.

Heresy and secret theology

Newton’s views on Christianity were arguably “heretical’ as they departed from the accepted form of Christianity of the day. There are two broad explanations of why heresy was considered so serious. The first reason was that the excesses of the pre-Christian pagan world were considered so egregious, and Christianity had forged such a sweeping and magnificent moral transformation of society, that Christian theology was effectively enshrined into law, and severe punishments were set for those who attempted to change Christian theology to something more resembling of Pagan thought. Protecting Christian doctrine was seen as synonymous with protecting the moral fibre of society. Any departure from orthodoxy was an opening which could lead back towards the dark times of pagan antiquity, their despotic tyrants, their endless wars, their paltry or absent human rights, and such a possibility was seen as something that must be fiercely defended against for the good of everyone.

The second explanation is somewhat more cynical, and is that the church had been infiltrated by secular forces, and bent to the wills and purposes of kings and queens to fulfil the secular goals of ambition, control, and power consolidation. Religion was used by rulers to manipulate, and one of the forms this manipulation took was cementing national cohesion. A country unified in faith would fight together against a common enemy, a country in which the boundaries of the state religion was beginning to unravel would not only be harder to motivate to fight an enemy, but would be more likely to disintegrate into internal fighting, and the monarch be taken down with the crumbling nation. Heretical challenges to established theology were therefore seen as attacks on national security, or on the personal security of the monarch. Hence positions of church authority were infiltrated and puppet clergy, puppet bishops, and puppet popes installed at the beck and call of monarchs and their secular power games, and the church used as an arm of state control, state investigation, and state punishment.

One or the other or a combination of these reasons meant that heresy was often treated among the most serious crimes a person could commit, and tended to be met with harsh punishments. In Newton’s case the punishment for heresy might have meant losing his position at Cambridge, or even a prison term. King James II was typically enthusiastic for a Monarch of the times for infiltration and co-opting of religious institutions for purposes of secular politics. All of this led him to pursue his theological studies in secret, and he filled notebook after notebook with arguments in support of the Son being greater than ordinary men but lesser than God. (“The son in all things submits his will to the will of the father which could be unreasonable if he were the equal to the father” he wrote, as one example.)

Only around the time of his death was it rumoured Newton had departed from conventional Anglicanism when he refused the Church of England sacrament and spent his final weeks working obsessively on an alternative Old Testament history. But the full extent of his interest in alchemy and Christian theology did not emerge until the twentieth century, when his scattered manuscripts were finally re-amassed by the British economist and collector John Maynard Keynes.

Conclusion: Physics and the occult

Newton died in his sleep on March 31st 1727. A marble inscription on his grave bore the words “mortals rejoice that there has existed so great an ornament of the human race.” Samuel Johnson said “if Newton had flourished in ancient Greece he would have been worshipped as a divinity.” Leibniz had said that in mathematics there was everyone else’s contributions since the world began, and then there was Newton, and Newton’s was the better half. But Newton himself was prone to modesty. “If I have seen further it is by standing on the shoulders of giants” he famously commented in mid-life. Shortly before his death he is said to have reflected “I do not know what I may appear to the world, but to myself I seem to have been only like a boy playing on the seashore, and diverting myself by now and then finding a smoother pebble or a prettier shell than ordinary, whilst the great ocean of truth lay all undiscovered before me.”

In assessing Newton it is worth remembering that gravity itself was initially considered an occult subject, for it involved the postulation of forces that we cannot actually see – we can only infer their existence from other facts. Newton’s work was responsible for elevating gravity from an occult to a scientific status. Other aspects of Newton’s Optics continued to sound largely occult even once his physics was accepted. His speculation in the Optics that gravity not only existed but could bend light was one such instance. This idea was not to move from the status of the occult to the scientific for another three hundred years, and the emergence of Einstein’s general relativity, which demonstrated that gravity could not only bend light, but could bend space and time as well. Such a suggestion had been beyond the speculation of even the most fervent occultists!

It is interesting, then, to contemplate the spiritual matters still considered taboo by today’s mainstream scientists, and what status will eventually be granted to these apparently occult beliefs in the future, as further light is shed on the truth by more adventurous scientists and philosophers. Newton, it seems, was ahead of his time in this respect, as in so many others. Transmuting the occult into the rational, and the rational into the spiritual, he was the archetypal alchemist, as well as the scientific genius in excelsis.

**********

This article is part of a series. Scientists covered in this series:

Isaac Newton

Charles Darwin

Alfred Wallace

James Clerk Maxwell

Max Planck

Kurt Godel

Albert Einstein

Georges Lemaitre

Jean Piaget

Werner Heisenberg

Erwin Schrodinger

Arthur Eddington

James Jeans

Donald Knuth

Francis Collins