For the man who went to a chapel and consulted with God before accepting the role, the Human Genome Project was more than a scientific endeavour. For Francis Collins, the once in human history project to map the genetic basis of human biological traits, was a moral endeavour to make the information freely available, and a fight against the private companies who sort to commercialise the venture and even patent sections of DNA. It was also a religious act – in so far as Collins was utterly convinced of the complementarity between science and religion – and of the role of science in the unfolding of God’s plan. Hence when Bill Clinton announced the completion of the project in June 2000 with the words “Today we are learning the language in which God created life, we are gaining ever more awe for the complexity, the beauty, the wonder of God’s most divine and sacred gift,” Collins was in full agreement.

Collins relationship with religion began in childhood, though not in the way we might have expected. Collins relates growing up on a ranch in the Shenandoah Valley in rural Virginia. He described his parents as “free thinkers”, and as “hippies before there were hippies”. Religion had no role for them, and they advised against taking it seriously. When sending him to learn music in a church choir, he recalls being told, “You should be respectful of what they’re doing, even if the stuff they’re talking about doesn’t make a lot of sense.”

Collins was home schooled by his mother on the ranch until the age of ten when they moved to the town to look after his aging grandmother and the children entered public schools. By the age of fourteen he was fascinated with science. Spiritually during his teenage years Collins recounts favouring a kind of vague agnosticism, though this was largely a matter of convenience. As he wrote in his book the Language of God:

“my assertion of "I don't know" was really more along the lines of "I don't want to know." As a young man growing up in a world full of temptations, it was convenient to ignore the need to be answerable to any higher spiritual authority.”

From here Collins followed a path into science, completing a PhD in quantum mechanics at Yale. By now his views had progressed into a determined and overt atheism. Even becoming the kind of “militant” atheist who publicly challenged others he came across who spoke of religion: “I felt quite comfortable challenging the spiritual beliefs of anyone who mentioned them in my presence, and discounted such perspectives as sentimentality and outmoded superstition.”

By the final year he was somewhat disillusioned by the prospects of quantum mechanics, noting that “most of the major advances had occurred fifty years earlier” and that the field had largely stood still since. Collins took a course in biochemistry, and then studied medicine at the University of North Carolina. By the third year of medical school Collins was actively involved in the care of seriously ill patients, and began to observe with curiosity and then fascination the deep roll that spirituality played in the lives and decisions of the North Carolina population. Having imagined that people’s religious beliefs would fade when faced with severe adversity he was surprised to find that this was not the case. He began to question his previous religious conviction in atheism, and finally, when asked by a religious patient about his own beliefs, had to admit that he simply had no idea why he held to atheism. Collins relates the incident in The Language of God:

"What struck me profoundly about my bedside conversations with these good North Carolina people was the spiritual aspect of what many of them were going through. I witnessed numerous cases of individuals whose faith provided them with a strong reassurance of ultimate peace, be it in this world or the next, despite terrible suffering that in most instances they had done nothing to bring on themselves. If faith was a psychological crutch, I concluded, it must be a very powerful one. If it was nothing more than a veneer of cultural tradition, why were these people not shaking their fists at God and demanding that their friends and family stop all this talk about a loving and benevolent supernatural power?

My most awkward moment came when an older woman, suffering daily from severe untreatable angina, asked me what I believed. It was a fair question; we had discussed many other important issues of life and death, and she had shared her own strong Christian beliefs with me. I felt my face flush as I stammered out the words "I'm not really sure." Her obvious surprise brought into sharp relief a predicament that I had been running away from for nearly all of my twenty-six years: I had never really seriously considered the evidence for and against belief.

That moment haunted me for several days. Did I not consider myself a scientist? Does a scientist draw conclusions without considering the data? Could there be a more important question in all of human existence than "Is there a God?" And yet there I found myself, with a combination of wilful blindness and something that could only be properly described as arrogance, having avoided any serious consideration that God might be a real possibility. Suddenly all my arguments seemed very thin, and I had the sensation that the ice under my feet was cracking."

And this began a long period of searching in which Collins examined the ideas expressed in the world’s religions.

In scientific circles Collins is known as the man who led the Human Genome Project. This was the effort to map the genetic basis of human biological traits conducted over twenty genome centres in six countries involving many of the best and most dedicated scientists on the planet. Bill Clinton compared it to Galileo’s work in astronomy and the discovery of the Americas – Collins role in science history is assured. In theological circles Collins is more likely to be noted for his synthesis of Christian theology with the ideas of modern biology and cosmology which was the result of this period of searching.

Now encountering adult and academic level treatments of religious issues he had previously dismissed, he realised “that all of my own constructs against the plausibility of faith were those of a schoolboy.” With more study and reflection the plausibility of God’s existence shone through in ever more convincing manner, until Collins could no longer deny the new sense that the universe made – “Faith in God now seemed more rational than disbelief.”

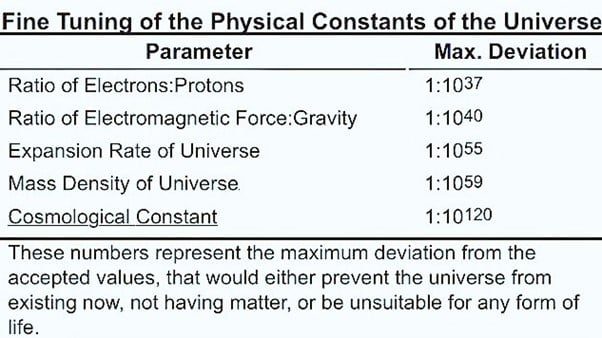

Collins conceived of a God evidenced by the moral imperative that pervades culture and history. But moral law was only one aspect of the evidence for God. God was a form of intelligence that played a role in setting certain parameters of the universe to ensure it would support life. For Collins certain “constants” were fixed from the beginning while everything else unfolded through Darwinian evolution. The fine-tuning of these constants is fully compatible with mainstream science and is widely acknowledged as a fact of modern cosmology. But why the universe should be fine-tuned in this manner remains a mystery. For Collins, the existence of a creative intelligence to explain the “fine tuning” is more likely than the most usual alternative explanation that our universe is one of a vast number of multiverses, and most of the others lack the fine tuning to become complex and support life. When a creative intelligence is deemed to be the cause of fine tuning, the synthesis of fine tuning and Darwinian evolution that results is known as “theistic evolution.” This position has been held by some of the most prominent biologists of the twentieth century including Theodosius Dobzhansky and Asa Gray.

Collins takes the human concern with morality as evidence not only of God, but of a God who is good. It was moral considerations which pushed him towards Christianity rather than a more general theism. If there are moral realities which have no convincing natural source, then it stands to reason they have a supernatural creator. This implies a personal God who takes an interest in actions. If some moral acts can be explained as a natural mechanism, then there seems to be a lot of others which have no natural explanation at all. Concern with morals is so pervasive across times, places and cultures that it can almost be regarded as a law of nature.

The explanation of acts of self-sacrifice that is attempted in secular biology is that humans are “programmed” to protect the gene pool of the species. A person might sacrifice their life in order to save a group of others as those people collectively have more genes to pass on. So the sacrifice is for the good of the species. An adult might sacrifice themselves to save a child because the child is younger and so will have more time to pass on their genes. There is no evidence that humans are “programmed” in this way, but even if they are, it is not difficult to think of examples of moral action which have no benefit for the gene pool, because the people who benefit are not more valuable genetically.

But the evidence for the moral law is not limited to examples of sacrifice. It is intertwined deeply with all that we do. In fact we see evidence of the pervasive reach of concerns about morality everywhere we look. In politics it is practically unheard of for political parties or political groups to simply assert that they are going to do something because they have the power and strength to do so. In almost all countries and almost all cases the desired actions are given an elaborate moral justification. Even the most depraved dictators in history have spent a great deal of time and effort justifying their actions from a moral perspective, even if it is necessary to invent things that are completely untrue in order to attempt to do so.

On social media discussion of political issues and current affairs are dominated by morality. No matter what someone on one side of the political spectrum has done, there will always be a search to compare it to something done by someone on the other side, in the hope that some moral high ground can be retained. Moral justification dominates all of our discussions. Confronting morality cannot be avoided.

Morality is a universal concern across times places and cultures. The ten commandments would capture the moral standards, more or less, expected in any society from anywhere in history. At times when leaders have temporarily led a society down an immoral path they have always had to work hard to convince their own population that the evil is needed, forced upon them, or at the very least a rightful and necessary retribution.

Yet how humans have managed to derive a sense of right and wrong is very difficult to explain. The naturalistic explanation is that our sense of what is right has develop through observing what is good for us collectively. But this presupposes a sense of good and bad in the first place. We can argue that what is good is what we observe makes people happy, such as food and shelter at the lowest level. But a reading of history has shown that those in power are often made more happy by causing suffering than by causing happiness. So it seems unlikely that we could have developed a sense of morality through simply observing what actions produce happiness.

For the theist there is a different explanation. Mankind is made in the image of God and is called upon to become like Christ – the manifestation of God in the world. We understand the difference between right and wrong and have a fixation on what is right and wrong because God does, and the seed of God is within all of us. This explains how acts of true self-sacrifice are possible. These acts, which have no natural explanation, are simultaneously evidence of the God that humans grow towards by acting in his image. In Christianity that image of God as the highest sacrifice takes a literal form and becomes fully real. The God it points to is a God who is good and holy. Other evidence would fit with deism, but the moral law points to a personal God who cares, and this fits with Christianity.

This also leads to another point that Collins brings out in his book. Moral action is a shared concern of the world religions. It is an aspect of God that all of them have got right to one degree or another. The world’s religions share many of the same truths for the very reason that the God they attempt to describe is objective and real. Much as different scientific theories will have aspects that they share because they are attempts to describe the same physical reality, so religions will share aspects with each other because they are attempts to reach the same spiritual reality. Moral concern is one thing they share. Another is the singular nature of God.

Collins also describes how his attempts to work towards greater knowledge of God fell flat. Making an effort to live a more pious life did not work. For him the way to know God was through something like the opposite of this effort: it was through the death of self will. Collins aligned himself with evangelical Christianity, which emphasizes the work of grace in the process of salvation. His personal experience fitted better with the Christian explanation of how the person comes to know God than religions like Buddhism or Islam, in which the person receives reward through their own efforts or works. So Christianity takes the central place, as the fullest revelation of truth, or the religious position which best explains the way the world is, though other religions can still say things that have value.

Fine-tuning refers to the extraordinary knife-edge on which some of the factors which have led to a complex universe have hinged. If even one of these factors were even slightly different then life would not be possible. A universe like ours consequently seems vastly improbably.

One example is the expansion rate of the universe. If the rate of expansion of the universe one second after the big bang had been slower by one part in one hundred thousand million million the universe would have quickly collapsed back on itself. If the rate of expansion had been faster by one part in a million the matter in the universe would have been flung too far apart for stars and planets to form.

In all fifteen physical constants exist which all have almost exactly the value they need to have in order for the universe to work. Even the most miniscule deviation in either direction would have resulted in a universe far shorter in duration or far simpler than ours which would have been incapable of supporting life.

Theistic evolution solves a large proportion of the “problem of evil” – the theological question of why God created a universe that contains evil. The animal kingdom is not a nice place. Animals survive by hunting and eating other animals and many have asked why God would create a universe which involved this apparently needless suffering on a vast scale. To the theistic evolutionist the problem is easily solved: God did not create animals or hunting. God only created a universe that would support life of some sort, and natural selection determined the details of life that evolved through chance interactions of genetic mutations and environments in which animals lived. In this way, a great many features of the universe and human experience that we might otherwise find incompatible with a God of love are explained.

Collins ends the discussion with a few quotations from well-known scientists who seem to agree with his take on theistic evolution:

Stephen Hawking:

“The odds against a universe like ours emerging out of something like the Big Bang are enormous. I think there are clearly religious implications”

Freeman Dyson:

“The more I examine the universe and the details of its architecture, the more evidence I find that the universe in some sense must have known we were coming”

Arno Penzias:

“The best data we have are exactly what I would have predicted, had I nothing to go on but the five Books of Moses, the Psalms, the Bible as a whole”

Collins spends a lot of time in the book debunking bad approaches to the relationship between Christianity and religion, including those which are favoured by a large number of American Christians. The primary targets are Young Earth Creationism and Intelligent Design.

Young Earth creationism (its supporters are known as YECs) is the belief that the earth was created in a literal six-day time period and that it must be under 10,000 years old. YECs accept that small changes can occur within a species by natural selection but reject macroevolution – the idea that one species can turn into another. Consequently they believe that humans were created in their present form with no ancestors around 10,000 years ago. Creationist theme parks in the USA consequently depict humans and dinosaurs coinhabiting the earth. According to a 2019 Gallup poll Young Earth Creationism is believed by 40% of Americans. Collins airs the widely held view in scientific circles that YEC is not scientifically defensible and does not stand up to even a cursory analysis:

“In general, those who hold these views are sincere, well-meaning, God-fearing people, driven by deep concerns that naturalism is threatening to drive God out of human experience. But the claims of Young Earth Creationism simply cannot be accommodated by tinkering around the edges of scientific knowledge. If these claims were actually true, it would lead to a complete and irreversible collapse of the sciences of physics, chemistry, cosmology, geology, and biology. As biology professor Darrel Falk points out in his wonderful book Coming to Peace with Science, written specifically from his perspective as an evangelical Christian, the YEC perspective is the equivalent of insisting that two plus two is really not equal to four. For anyone familiar with the scientific evidence, it is almost incomprehensible that the YEC view has achieved such wide support, especially in a country like the United States that claims to be so intellectually advanced and technologically sophisticated.”

Collins suggests that YEC views are not required by the Biblical text. Genesis is written in an allegorical rather than historical or factual style. The former head of the Human Genome Project then reminds us that wrong interpretation of scripture can have negative consequences for the church, and relates the Galileo incident as an example of this. Numerous points are worth bringing out from this. Not all Christians were against Galileo. He was supported by Jesuit academics, and many modern commentators on the issue have argued that the church scientists who opposed him were being more rational and critical than Galileo himself, whose theory lacked evidence at the time it was proposed and was not finally established with certainty until long after his death. The main error of the church was a faulty understanding of scripture, not of science. Genesis was not intended to be taken literally, and was not taken literally in previous ages or by central church figures. To what extent the Catholic Church at this point was primary a secular political institution, and was attempting to defend a literalist interpretation of the Bible for purposes of political and military cohesion, and therefore to what extent they were really representing Christian thought at all rather than exercising secular and political power, is also open to considerable debate. Collins highlights what he believes was an error in attributing literalism to passages which were never intended to be literal.

Collins own view is that passages of the Bible which were intended as literal and accurate history can be clearly differentiated from allegorical and symbolic passages based on the style of writing in comparison to other similar writings form the period. He takes much of the New Testament as literal history – to the extent that in a recent podcast he stated that proof that Jesus had not risen from the dead would be all it would take to destroy his belief in Christianity – but he is equally adamant that many passages were never intended literally, and were almost never taken as literal in ancient times.

Finally, Collins argues that he simply does not find it natural to assume that God is a deceiver who has created apparently overwhelmingly convincing, but fallacious, evidence for an old earth. Building such “tricks” into the universe would be entirely necessary for young earth views to stand any chance of being correct.

Intelligent Design is the belief that certain human and animal features show evidence of a designer. Collins rates Intelligent Design as a more serious hypothesis than Young Earth Creationism. It stands less obviously at odds with established scientific findings and interpretations, and requires better analysis and subtler arguments to dismiss. Nonetheless, it should be dismissed as it does not currently find enough support. Collins then gives various examples of features that appear to adhere well to Intelligent Design, but which do not withstand a more thorough analysis.

Intelligent Design rests on the unlikely complexity of nature. Michael Behe draws attention to complex structures involving multiple proteins, the absence of any one of which would have prevented the functioning of the unit they comprise. Such structures may appear unlikely to have arisen through natural selection as earlier and simpler versions of the units would not have had any role and should not have been selected for. This is known as “irreducible complexity.” Behe suggests that these units come “pre-programmed” as packages of genes designed to activate when the time is right and therefore show no evolutionary trail of simpler versions of the unit. The flagship example of the Intelligent Design Community is the flagellum (propeller) of bacteria, comprising of more than thirty proteins and several interconnected parts.

But this and other examples given by the Intelligent Design community have generated a large literature of discussion and with further analysis can be shown to have evolved gradually after all. The flagellum may have initially had a completely different purpose such as a weapon to inject toxins, a feeding tube, or something more like a basic leg for pushing the organism away from objects. The flagellum may have passed through numerous different early uses and numerous different roles as it gradually evolved into the propeller structure we see today. Other apparently irreducible units such as the human blood clot cascade and the eye can be also shown to have had functions at earlier stages of development. The eye may have had a long history as a patch of skin that is slightly more sensitive to light than other areas, and provided slightly more information to the nervous system, which would have given creatures with this skin sensitivity a small evolutionary advantage.

Two other areas that Collins gives some attention to are the big bang and DNA. The big bang, in Collins words, “cries out for a divine explanation”. The big bang is extremely well evidenced by well-established scientific theory that has been accepted by almost all cosmologists for decades. It also appears to square extremely well with the monotheistic notion of creation of the universe from nothing. All scientific laws breakdown in “Planck time” – the earliest moment of existence about which we appear to be able to know nothing. Science appears to have established, by its own methods, that it can tell us nothing about the moment of creation. “I cannot see how nature could have created itself,” writes the former head of the Human Genome Project, “only a supernatural force that is outside of space and time could have done that.” In this regard, he quotes a passage from the astrophysicist Robert Jastrow which is both amusing and enlightening:

"At this moment it seems as though science will never be able to raise the curtain on the mystery of creation. For the scientist who has lived by his faith in the power of reason, the story ends like a bad dream. He has scaled the mountains of ignorance; he is about to conquer the highest peak; as he pulls himself over the final rock, he is greeted by a band of theologians who have been sitting there for centuries.”

A different type of argument stems from the complexity of DNA. DNA seems too complicated to have occurred by chance. Collins argument here is similar to Intelligent Design, but unlike other elements of focus in Intelligent Design, he argues that it is currently not adequately explained by conventional biology.

We have completely failed to reproduce the RNA component of DNA in laboratories. The unlikely complexity of DNA led Francis Crick, co-discoverer of the structure of DNA along with James Watson, to conclude that DNA must have been created elsewhere in the universe and have travelled to earth on an asteroid as it was so different to anything else around on earth at the time and it seemed impossible to have been created by evolution from other earthly substances. This hypothesis is known as panspermia. But panspermia does not solve the problem either. Panspermia is not a solution as it simply pushes the creation of DNA to some other location. How a self-replicating molecule with information carrying properties that is even capable of checking its own work can have arisen spontaneously from far simpler compounds remains a mystery.

Collins warns against definitively pinning divine intervention or design to the creation of DNA however, as so many units, features and organisms which seemed to be examples of this have turned out to have conventional explanations. The origin of DNA is currently unexplained but that does not necessarily mean a divine entity played a role in its formation:

“Given the inability of science thus far to explain the profound question of life's origins, some theists have identified the appearance of RNA and DNA as a possible opportunity for divine creative action. If God's intention in creating the universe was to lead to creatures with whom He might have fellowship, namely human beings, and if the complexity required to start the process of life was beyond the ability of the universe's chemicals to self-assemble, couldn't God have stepped in to initiate the process? This could be an appealing hypothesis, given that no serious scientist would currently claim that a naturalistic explanation for the origin of life is at hand. But that is true today, and it may not be true tomorrow. A word of caution is needed when inserting specific divine action by God in this or any other area where scientific understanding is currently lacking. From solar eclipses in olden times to the movement of the planets in the Middle Ages, to the origins of life today, this "God of the gaps" approach has all too often done a disservice to religion (and by implication, to God, if that's possible).”

The big bang and DNA are not definitive proof of divine creation and stand open to correction by future developments, but at the moment the big bang in particular should certainly arise curiosity in both believers and atheists.

Collins thoughts on religion can be summed up as a science based theistic evolution. God set the universe in motion and intentionally created a universe that would support life of one kind or another. From there, the development of life was left to the processes of natural selection and survival of the fittest. Theistic evolution is wholly compatible with traditional Christianity. The resurrection as described in the Gospels was a real historical event. The Bible contains both literal and allegorical passages, and the style of text makes clear which is which. The Biblical account of creation is perfectly compatible with today’s cosmology and biology when understood in this way. This was the usual way for the Bible to be understood in ancient and medieval times. The act of doing science could also be a form of worship: “I think scientist-believers are the most fortunate. We have the opportunity to explore the natural world at a time in history where mysteries are being revealed almost on a daily basis. We have the opportunity to perceive the unravelling of those mysteries in a special perspective that is an uncovering of God’s grandeur. This is a particularly wonderful form of worship.”*

*Quotation from International Journal of Frontier Missions (2003). Other quotations are from the Language of God (2007) except where otherwise indicated in the article text.

**********

This article is part of a series. Scientists covered in this series:

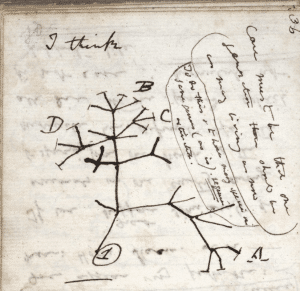

Isaac Newton

Charles Darwin

Alfred Wallace

James Clerk Maxwell

Max Planck

Kurt Godel

Albert Einstein

Georges Lemaitre

Jean Piaget

Werner Heisenberg

Erwin Schrodinger

Arthur Eddington

James Jeans

Donald Knuth

Francis Collins