When James Murphy asked Albert Einstein to write an introduction to a book containing Max Planck’s essays in 1932, Einstein initially refused, stating that it would not be fitting for Planck’s book to contain an introduction from a lesser luminary. Earlier in the conversation Einstein had made it clear he considered quantum theory, which Planck discovered, to be a greater breakthrough than relativity. Yet by the end of his career Planck was more engaged with lecturing on the nature of God and religion than he was with conducting scientific research. Planck believed in a God who created the universe and was present in its unfolding, a God who saw our private thoughts, and an eternal realm to which we would journey after death. He prayed before meals and attended church, serving as a church elder for twenty-seven years. Even his great scientific discovery – the Planck constant – he was quick to imbue with theological implications. As he related in a Florence lecture:

“Having studied the atom, I am telling you that there is no matter as such! All matter arises and persists only due to a force that causes the atomic particles to vibrate, holding them together in the tiniest of solar systems, the atom. Yet in the whole of the universe there is no force that is either intelligent or eternal, and we must therefore assume that behind this force there is a conscious, intelligent Mind or Spirit. This is the very origin of all matter.”*

For Planck science was one route to God. He referred to it as an indirect route. It contrasted with the direct route to God, which was through the sacrament of conscience. As he commented in the 1937 work Religion and Science, both these approaches lead to the same result.

Religion was a motivating factor for Planck’s scientific research, and he noted the same motivation in other great scientific thinkers dating back to Johannes Kepler’s heliocentric theory. At the same time science could never fully take the place of religion, because science was an attempt to substitute the thrill of discovery from its true nature as religious discovery. Science could clarify some religious claims: Planck was highly critical of the claims of contemporary occultists and mediums, and felt that these claims brought true religion into disrepute. But ultimately true religion was beyond science and beyond scientific investigation.

Planck had a somewhat unusual relationship with Christianity, juggling a lifetime of church service and prayer with criticism of some aspects of what the average Christian at the time might have believed, leading to some biographers characterising him as a deist. At the same time his written work on religion was being championed by both Protestant and Catholic leaders. His relationship with Christianity was also at the centre of his criticism of the Nazi regime and of the religious movements the Nazis created and tried to impose in place of Christianity.

Life and career

Born in Kiel, a small fishing community bound by fjords on the Northern coast of Germany, Planck showed few signs of brilliance while in school. He usually placed between third and eighth in his year. His success was a case of the slow maturity of ideas coming to fruition through years of study. As we shall see, in the dark years of his early career, religion appeared a significant drive in his pursuit of science, and his later religious works stressed the complimentary motivations of science and religion.

Planck himself had always claimed to have no great gift for physics. He wrote at the end of his life that he had preferred physics to a career in music or history for philosophical reasons rather than greater ability. At the age of seventeen he entered the University of Munich. It was here he expressed to Philipp von Jolly that he had no desire to discover anything new, only to understand as much as possible of what had already been achieved. (Years later, when Planck had the Nobel prize and his work had revolutionized world physics, the humble professor was still attempting to down play its significance and look for ways to integrate quantum theory back into classical physics!)

By 1877 Planck was studying in Berlin with Gustav Kirchhoff, Karl Weierstrass, and the intellectual giant and polymath Herman von Helmholtz. Helmholtz’s notion of the Principle of Least Action was to prove an important component of Planck’s theology.

Two years later he had completed his doctoral dissertation on thermodynamics. Thermodynamics was at the time a minority interest, which went against the dominant principles of the universe that Newton had revealed. Thermodynamics claimed to bring direction to the universe, because thermodynamic processes were not reversible. In his thesis Planck clarified Clausius’s second law of thermodynamics, bringing out more explicitly the irreversibility of the universe and of time itself. A cup of coffee will always cool over time and never naturally become warmer. This process is known as entropy, and contrasts with a body travelling through space, whose flight can be reversed. Unlike the laws of motion, thermodynamic processes cannot be reversed. This ensures that the universe could not run backwards, and hence creates the irreversible “arrow of time.”

Thermodynamics was a fringe area of research. Planck could find only one other thinker at the University of Berlin with an interest in it, and estimated in 1900 that not more than four physicists in the world were focused on the conflict between atomism and entropy. Kirchhoff was critical of the thesis, Helmholtz, with whom Planck was now close friends, declined to comment. Somewhat frustrated, and having had several letters asking for a response ignored, Planck made an uninvited five hundred kilometer journey from Berlin to the house of Clausius, on whose work his thesis focused, in order to press him for comment, only to find him on holiday.

Above: A grainy photo of the young Max Planck from the period he was pursuing his early work on entropy. Enjoying little early career success, Planck related later in his life that religion was a strong motivation for his pursuit of science during this time. This research eventually lead to the discovery of the Planck constant which was to change international physics. Along with the Principle of Least Action it was also a core principle of his natural theology.

But Planck persisted. For the newly graduated physicist, entropy had theological implications. It provided a scientific basis for “teleology” – the notion that the universe was progressing towards a perfect state. If the universe could not flow backwards it must flow forwards if it flowed at all: if flowing forwards it must complexify and deepen as time passed. This fitted both with traditional theologies such as the Biblical notion of progress from Genesis to Revelation and the subsequent completion of “God’s plan”, and also with more modern deistic theologies in which life evolved towards some kind of utopic future state.

While Newton and Einstein had changed world science when still in their twenties, Planck spent this decade living with his parents wondering if he could ever make a living from physics. Much later in his life Planck was to note the motivation that religion played for Johannes Kepler in his hypothesis on heliocentric theory. It is likely a similar drive was at work in the young Planck as he persisted with promoting the significance of entropy.

A lecture to the German Physical Society on thermodynamics in 1889 was not met with enthusiasm or even polite applause, but with silence which was only broken by the chairman. This was something of a nadir for Planck, and from here his fortunes rapidly changed.

In 1892 Planck was nominated to the Berlin Academy by Helmholtz and two years later he began work on black body radiation – the mysterious glow which emanates from all things. It was here in 1899 he discovered the Planck constant, and unlocked the modern age of physics. His seminal paper On the Distribution of Energy in a Normal Spectrum followed in 1900. This work gave birth to quantum mechanics. Through persistence Planck had taken the concept of entropy from obscurity to a core principle of physics. By 1891 his graduate thesis, initially ignored by even his tutors, had been passed around so much it was falling apart. James Jeans summarized that the principle of entropy was initially “criticized attacked and even ridiculed, but it proved brilliantly successful and ultimately developed into the modern quantum theory.”

The Planck constant, h, is the value 6.626*10 to the power of minus 27 joule-hertz. Planck had shown that energy did not flow as was previously held by the majority of physicists, but was emitted in units. The Planck constant provided an insurmountable constraint on this emission of energy in two ways. Firstly, no energy could be emitted in units smaller than the Planck constant. Secondly, all energy emitted had to be whole increments or “integrals” of the Planck constant, so we can have energy units of 2h, or 3h, or 4h, etc, but energy units cannot be of values between 2h and 3h, or 3h and 4h. These discontinuous energy units were known as quanta, and this concept was revolutionary to the physics of energy. The constant, h, which Planck derived also had religious implications. For Planck it confirmed that nature obeyed ordered laws down to the smallest degree – scientists dating back to Galileo had taken these ordered laws as a sign of God’s hand. It also imbued the physical universe with teleology down to the lowest level – it confirmed Helmholtz’s Principle of Least Action in the world of microphysics. The emission of energy quanta that h described could not run backwards any more than a standing cup of coffee could get warmer rather than colder. The Planck constant was the ultimate revelation of God in nature, giving the universe not just laws but direction and progression. For Planck, God belonged alongside atoms, in the category of things that we cannot observe directly, but whose existence we can infer.

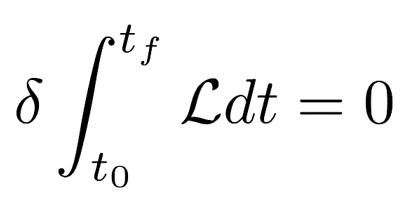

Above: The Principle of Least Action. Planck’s work helped to show that the principle continued to apply in quantum and relativistic physics as well as in classical physics. The universe was compelled to follow an optimal energic path on all levels. This had teleological implications for the philosophy of religion, as it confirmed there was a direction to the universe, and therefore no contradiction between science and the idea of the universe progressing towards a perfect state or divine fulfillment. Planck also held that conscience attempted to impose a similar teleological effect on human psychology and on history, but humans had free will and so could choose whether or not to follow it.

In 1905 Planck threw himself into relativity after reading Einstein’s paper. Planck is often credited, along with Arthur Eddington, of having “discovered” Einstein, and the acceptance of Einstein’s ideas owed much to Planck’s attention. In 1906 he published a paper showing that the Principle of Least Action continued to apply in the world of special relativity. Teleology had survived the two largest conceptual shifts in our understanding of physics since Newton. Planck was first nominated for the Nobel Prize in 1908 on the grounds that his work had proven the existence of the atomic world which had been broadly accepted since the early twentieth century, but lost out to Gabriel Lippmann after Lorentz had shown a discrepancy between Planck’s work and ordinary physics.

In 1908 Planck returned to cavity radiation, and modified his theory to include the restriction of resonator energy to integral multiples of hv. By this time Planck had already proposed the notion of quantized spacetime, in which time and space have the same discontinuities as quantum entities – this plays a key role in current attempts to integrate quantum theory with relativity. (Planck is also credited with discovering the zero point energy – the energy which remains in an object even at absolute zero.)

By 1910 Einstein, Nernst and others had applied the reworked theory far beyond cavity radiation. Prominent physicists of the day including Lorentz, Einstein, and Sommerfeld all agreed that the Planck constant brought something completely new to physics, though they disagreed about exactly where it would lead. So much so that 1911 saw the first of what became known as the Solway conferences. A council of twenty one of Europe’s leading physicists were convened to discuss Planck’s work at the expense of the Belgian businessman and philanthropist Ernest Solway.

In 1919 Planck was finally awarded the Nobel prize, which was actually the prize for the year 1918 that had not been awarded due to the war. This was generally regarded as long overdue. The prize had evaded him largely because, despite the influence of quantum theory, its enigmatic nature had failed to yield a coherent explanation of why the things it predicted happened. In 1919 Sommerfeld presented the committee with his argument that physics was now the physics of quanta. Leading physicists including Lorentz, Born, Wien, and Einstein were adamant the prize should go to Planck.

And so the waters finally parted for Planck and the hardworking and conscientious Berlin professor arrived at the pinnacle of the scientific world. But even receipt of the Nobel Prize did not prevent him from downplaying the significance of quantum theory, and he continued to try and reduce its role by fitting it back into classical structures. He remained convinced that quantum theory would eventually be regarded as expanding current physics, rather than providing a complete reorientation.

Regarded as a late developer and possessing no special gift for physics in his early career, Planck’s story provides a prime example of how academic progress really happens. Thousands of academics whose names are not remembered lay the foundations for progress, by and large, through failed ideas. But those who provide these failed ideas are just as important as the luminaries whose ideas are proven correct. It is only through tens of thousands of failed projects that unproductive areas of inquiry can be identified and set aside and those who make the breakthroughs know where to look. Academia is a team effort in which all contributors play rolls that are arguably equally important. It might be added that brilliant minds have the best chance of taking advantage of the opportunities that arise, but only once the ground has been prepared for them by the diligent work of thousands who came before and around them whose work – by its successes equally by its failures – made it clear where to look.

As early as 1913 Planck gave an address to the Berlin Academy which criticized those who claimed science without spirituality could provide a satisfactory worldview. But his attempts to contribute to discussion regarding science and religion began in earnest in 1930 with the publication of Faith and Science. His book Where is Science Going published in 1932, and his 1937 essay Religion and Science are his best known religiously themed works. From 1937 until his death he organized regular conferences on science and religion throughout the Baltic. His aim now was to provide a more comprehensive and wide ranging theory which brought science, philosophy, and religion into a coherent whole.

Planck’s religious writing

Such were the breakthroughs that physics was making in the early decades of the twentieth century that the leading scientists inadvertently took on the role of philosophers as the public looked to them for guidance in a universe that was rapidly changing. Almost universally, the great scientists of the period looked beyond science to philosophy and theology for their own answers.

The theism of the scientists of the period was generally based around logic and observation. For some this did not prevent embrace of traditional Christianity with all of its radical supernatural claims. Others tended towards deism. Even those who wanted nothing whatsoever to do with the radical and supernatural aspects of religion still arrived at the God of natural theology, which provided the basis for modern Christian thought. The evolution of Darwin and Wallace, and the thermodynamics of Planck, provided core principles of modern teleological theology.

Where is Science Going? (1932)

In the 1932 book Where is Science Going? Planck addressed several philosophical and religious themes in relation to the history of physics. The opening chapter gave an overview of the movement from electromagnetism, to relativity, to quantum theory. Planck then moved to spiritual themes, addressing conscience and free will. Planck was a strong advocate for conscience and the importance of following its demands:

“His own conscience is the tribunal of that law of moral responsibility and there he will always hear its promptings and its sanctions when he is willing to listen. It is a dangerous act of self-delusion if one attempts to get rid of an unpleasant moral obligation by claiming that human action is the inevitable result of an inexorable law of nature.”

Planck contrasts human consciousness with the world of physics in which everything is determined by prior actions. Human consciousness, according to Planck, has a transcendental element. Human consciousness breaks the chain of causation because it is able to reflect upon itself. Humans are uniquely able to determine their own actions. Free will might be strongest of all in geniuses, who escape furthest from the causal chain, allowing their extreme freedom of ideas.

Planck’s constant provided the teleological mechanism of the universe. Planck saw teleology in all things including morals, and religion was the vehicle through which the teleology of morals unfolded. Teleology pulled forward the psychological universe through conscience. But unlike physical teleology which was inevitable, psychological teleology could be resisted. Conscience made its demands known to everyone, but everyone was also free to resist those demands.

Planck also discussed miracles. He was an outspoken critic of miracles, though what he really meant by this in the 1932 work seems to be contemporary claims of miracles. For Planck “miracles” referred to all of the claims of the burgeoning area of mediumship and occultism, which involved a great deal of fakery and brought religion more generally into disrepute. There was no way of knowing if a real miracle had ever taken place, as it was by definition beyond the bounds of known science to investigate. “Religion,” as Planck put it, “belongs to that realm that is inviolable before the law of causation and therefore closed to science.” Nonetheless Planck took to task Steiner, Spengler, and other “populisers” of miraculous claims.

The evidence of God was unveiled by both studying the workings of the universe, and belief in God created a feedback loop that pulled forward human understanding. Teleology is both revealed by science and provides the impulse to draw knowledge forwards:

“There can never be any real opposition between religion and science; for the one is the complement of the other. Every serious and reflective person realizes, I think, that the religious element in his nature must be recognized and cultivated if all the powers of the human soul are to act together in perfect balance and harmony. And indeed it was not by accident that the greatest thinkers of all ages were deeply religious souls.”

He cites the contrasting cases of Kepler and Brahe as an example:

“Brahe had the same material under his hands as Kepler, and even better opportunities, but he remained only a researcher, because he did not have the same faith in the existence of the eternal laws of creation. Brahe remained only a researcher, but Kepler was the creator of the new astronomy.”

At the end of the book, transcripts of a discussion between Planck, Einstein, and Murphy are published. In the transcripts Planck expresses the opinion that the churches were failing to excite the spirit of discovery as they once had, and other avenues of discovery such as science were taking their place. But this was only by “stimulating the religious reaction indirectly.” And hence “science as such can never take the place of religion.” Like many great scientists, he felt that science and religion shared the same heartbeat.

Above: By midlife Planck was juggling his status as Nobel laureate and custodian of German science with his religious writing and lecturing, while serving as an elder at his local church.

Religion and Science (1937)

Another of Planck’s notable works on religion was the 1937 essay Religion and Science. This was extremely popular, and was reprinted five times in two years. It was declared by the Protestant Union Press to be the end of a century of conflict between science and religion, and met with equal approval in Catholic Belgium. In this work Planck stated that he considered the belief in any miracle harmful, and not just the dubious claims of contemporary miracles among occultists. Belief in miracles is ammunition for atheists, and religion would be better off without these claims:

“Under these circumstances, it is no wonder that the atheist movement which calls religion an arbitrary delusion invented by power-hungry priests and which has nothing but words of derision for the pious faith in a supreme power above man, is eagerly taking advantage of the progress of scientific knowledge; allegedly in alliance with natural science, the movement continues to spread at an ever quickening pace its disruptive influence over all nations and classes of mankind. I need not go here into a more detailed discussion of the fact that the victory of atheism would not only destroy the most valuable treasures of our civilization, but — what is even worse — would annihilate the very hope for a better future.”

He proceeds to give a fairly masterful account of the evolution of multiple religions, which is rather similar to the recent work of John Hick, and is worth quoting at length:

“Religion is the link that binds man to his God. It is founded on a respectful humility before a super-natural power, to which all human life is subject, and which controls our weal and woe. To be in harmony with this power' and to enjoy its good graces, is the incessant endeavor and supreme goal of the religious person. Only in this way can he feel protected from the foreseen and unforeseen dangers, which threaten him in this earthly life, and can he enjoy that purest of all happiness, the inner peace of mind and soul that is secured only by a firm link to God and by an unconditionally trusting faith in His omnipotence and benevolence. In this sense, religion is rooted in the consciousness of the individual.

But its significance transcends the individual. Instead of each individual possessing his own distinctive religion, religion seeks to become valid and meaningful for a larger community, for a nation, for a race, and ultimately for all of man- kind. For God is the sovereign of every country on this earth; the whole world with all its treasures and all its horrors is subject to Him, and there is no portion either of the realm of nature or of the mind without His omnipresence.

Therefore, the spirit of religion unites its adherents in a universal alliance, and sets before them the task of mutually acquainting each other with their articles of faith and giving them a common manifestation. But this can be accomplished only by clothing the substance of religion in a definite external form, suitable because of its intuitive clarity for the creation of a mutual under- standing. In view of the great diversity of the races of man and of their ways of life, it is only natural that this external form is quite different in different parts of the world, so that a large variety of religions have come into existence in the course of the ages, A common feature of all of them consists in the rather natural assumption of a personified or at least an anthropomorphic deity. This leaves room for the most diverse concepts of the attributes of God. Each religion has its own distinct mythology and also its own dis- tinct rituals, elaborate to the most minute details in the more highly developed religions. These are the source of certain interpretive symbols of religious worship, which are capable of acting directly on the imagination of the great masses, arousing their interest in religious matters and giving them a certain understanding of the deity. Thus, a systematic unification of mythological traditions and a strict observance of solemn ritualistic customs invest the worship of God with an external symbolical form, and centuries of incessant observance and systematic education of generation after generation increase the significance of such religious symbols. The holiness of an unfathomable deity is translated into the holiness of intelligible symbols.”

The symbols nonetheless are symbols of something real, though inexpressible:

“On the other hand, a religious symbol always points beyond itself. Its significance is never exhausted by its own features, however much veneration it may enjoy because of its own age and the operation of a pious tradition. It is important to emphasize this because the development of civilization makes the high esteem enjoyed by certain religious symbols subject to certain inevitable changes in the course of the centuries, and it is in the interest of a genuine spirit of religion to establish the fact that what stands behind and above these symbols is unaffected by such changes.”

He then goes on to attack the techniques of the atheism. Interestingly these passages read like a rebuke for the “new atheist” movement which sprung up sixty years later and was still based on the same techniques:

“But the overrating of the significance of religious symbols opens the gates to another, far more serious danger of an onslaught by the atheistic movement. It is one of the favorite techniques of the atheists, whose aim is the undermining of every true religious feeling, to direct their attacks against old-established religious rites and customs and to hold them up to ridicule or contempt as outmoded anachronisms. Through such attacks against symbols, they expect to hurt religion itself, and the more strange and conspicuous those views and customs are, the easier it is for the atheists to score a success. Many a religious soul has succumbed to these tactics. Against this peril there is no better defense than to understand clearly and thoroughly that a religious symbol, be it ever so venerable, never represents an absolute value but is always only a more or less imperfect sign of something higher and not directly accessible to human senses.”

In this way the attacks of atheism on religion invariably miss the target altogether. Both the religious and scientific man begin from a position of faith. The religious man’s faith is in the existence of a God which he cannot yet prove, and the scientific man’s faith is in the existence of an objective world which he cannot prove. Through science we discover the laws of nature, a rational world order, the Principle of Least Action, and teleology. Thus the scientific man arrives at God in a different way to the religious man, but nonetheless eventually identifies the “world order of science with the God of religion.” One difference remains: for the religious man God exists at the beginning of his reflection, for the scientific man God appears at the end.

The essay draws to a close with a hat tip to the certainty of experience which is known by many religious believers, and is better evidence, in Planck’s view, than the testimony of those who claim to have seen miracles:

“To the religious person, God is directly and immediately given. He and His omnipotent Will are the fountainhead of all life and all happenings, both in the mundane world and in the world of the spirit. Even though He cannot be grasped by reason, the religious symbols give a direct view of Him, and He plants His holy message in the souls of those who faithfully entrust themselves to Him.”

This though, is just one route to God. The other is the scientific route, which attracts a different soul:

“In contrast to this, the natural scientist recognizes as immediately given nothing but the content of his sense experiences and of the measurements based on them. He starts out from this point, on a road of inductive research, to approach as best he can the supreme and eternally unattainable goal of his quest — God and His world order.”

One of the remarkable things about the religion of Planck, like the other deists we have covered in this blog series, is that he could dispense with much of the claims of religion that those religions would consider essential, while still never doubting the existence of God. For theists scientific deism is evidence that the concept of God still coheres for the skeptical personality and that even the denial of key aspects of particular religions does not prevent the concept of God as a whole from shining through in a manner that is still recognizable to more traditional adherents. Perhaps this is why Planck’s essay went down so well with European Christians.

Planck and Christianity

Rather like the quantum world which he was to bring into our awareness, Planck’s views on religion remained imprecise and contradictory. Nonetheless, this was a subject on which he wrote and lectured widely throughout his life. He sometimes expressed ideas that fitted better with deism than Christianity, while in other respects his God was very much like the God of Christian theology, and he kept up a relentless and committed attendance of a Christian church. Planck’s religious expositions focused around the traditional Godhead, and the higher being he described clearly drew much inspiration from Judeo-Christianity:

“Now, in the sight of God all men are equal. Even the most highly gifted geniuses, such as a Goethe or a Mozart, are but as primitive beings the thread of whose innermost thought and most finely spun feelings is like a chain of pearls unrolling in regular succession before His eye. This does not belittle the greatness of great men. But it would be a piece of stupid sacrilege on our part if we were to arrogate to ourselves the power of being able, on the basis of our own studies, to see as clearly as the eye of God sees and to understand as clearly as the Divine Spirit understands.”

This is a God who see our thoughts and the desires of our hearts. This is very reminiscent of the Christian God preached in churches to this day. In a 1946 letter to Neuberg he professed belief in “another world, exalted above ours, where we can and will take refuge at any time.”

Yet a few months later he disavowed believing in the personal God altogether in a letter to W. H. Kick. The flat out denial of the personal God at the end of his life does not fit at all easily with his habits of praying during the day and his committed attendance and service as an elder in the Lutheran Church. The position of elder would undoubtably have required membership of the Church, and a statement of allegiance to the beliefs. The role was also rather like an assistant pastor, and would have involved praying with church members in need and other similar supportive roles. To hide his true beliefs for a lifetime and pretend in these situations simply doesn’t seem very plausible. Neither would there be any reason to do it. So the denial of Christian belief in the letter is puzzling. Planck was showing signs of dementia at this stage, but the comment shows enough continuity with his 1937 essay for a dismissal of the letter on grounds of failing mental faculties to be too simplistic.

Consequently some biographers have characterized Plank as a deist, while other summarizers have described him as a devoted Christian who was also extremely tolerant of other religions. “Planck never lost his deep faith and belief in a personal God,” concluded Robitaille in 2007. We will probably never know the real truth of Planck’s belief in this regard, and are left holding two contradictory pieces of a puzzle which do not fit easily together. Wherever Planck really stood on the issue, Christianity became the focus of much of the relationship with and resistance to the Nazi’s.

Above: The madness of Nazi Germany saw Einstein derided while Hitler was hailed as a genius comparable with Galileo, Kepler and Newton. Planck attempted to dilute the Fuhrer’s attempts to use religion to manipulate the population.

The Nazi’s knew that the approval of the man respected as the father figure of German science was important for their propaganda campaign. As revealed in letters and notes, Planck believed he could do more good within Germany as a free man, and attempted to steer a course where he traded a degree of approval for Nazi policy for the ability to continue to lecture and publish, while often slipping covert criticism of the regime into his lectures and publications. The Nazis for their part appeared prepared to tolerate this as the price paid for the propaganda victory of having Planck remain in Germany, while many German scientists fled as WW2 loomed. Others they drove away, especially Jewish scientists. Einstein, who left for America before the war, was derided. Hitler on the other had was exalted by Nazi physicists Stark and Lenard, as a “genius” to be compared to Galileo, Kepler and Newton.

Planck’s own politics was a mix of conservatism and traditional German values with more liberal sentiments particularly in regard to feminism. He was a great promoter of women in science and enabled the career of Lise Meitner, the Jewish physicist who came close to a Nobel Prize. The reluctance and conflict Planck experienced in tolerating the Nazi regime is summed up in this report from the New York Times in 1936: “Planck stood on the rostrum and lifted his hand half high, and let it sink again. He did it a second time. Then finally the hand came up and he said ‘Heil Hitler.’”

Loosely based around Nietzsche’s “will to power” thesis, Hitler pushed a vision of competition among humans and human races similar to competition in the animal kingdom in which the strongest survived. People or races who resisted the innate drive to participate in this competition were considered weak or even psychologically sick. Hitler’s lifelong dislike of Christianity stemmed from this perceived weakness. For the Nazi’s competition and violent struggle was the natural state of groups of humans, and should not be avoided. Planck’s philosophy of free will challenged this. Planck believed that the capacity of thought to reflect upon itself broke the chain of physical causation, and allowed for genuine self-determination of actions. This distinguished humans from animals. Planck considered liberal Christianity to be the moral code which had lead the Western world to flourish: Christ’s teachings contained the essence of all true religions. This was direct contradiction of Nazi ideas, and he gave these feelings covert airings in his lectures.

The Nazi approach to Christianity was two-fold. Initially they required instability in order to come to and consolidate power, and rally people around Hitler’s antisemitic hate preaching. In order for hatred to take hold it was necessary to weaken the grip of Christianity. Hitler’s first job with the DAP (forerunners of the Nazi party) was to spread anti-Christian propaganda: the Nazis forerunners already realized that Christian ethics needed to be diluted as much as possible in order for Nazi values to spread. As Hitler wrote, Christianity “sows seeds of decadence such as forgiveness, weakness, humility and the denial of the evolutionary laws of survival of the fittest.” Soon after coming to power Hitler created the Reich Church, a movement re-modelled from Protestant Churches intended to undermine the peaceful aspect of Christianity, and replace it with a more warlike version. Later he created the German Faith Movement, a neo-Pagan alternative to Christianity which involved Sun worship, replacing the cross with the swastika and the Bible with Mein Kampf, and Positive Christianity, a version of Christianity which did not require any belief in the creeds or in Jesus as the Son of God, instead faith was placed in Hitler as the bearer of a new revelation. The Nazis promoted German neo-Paganism, or Eastern philosophies, in place of traditional Christianity. The perceived nihilism of the East was far preferable to them than Christian ethics.

Where order was required the Nazi’s were much more likely to encourage Christianity. While attempting to weaken it in the general population they encouraged it within their own armed forces, and even sent troops into battle with the Iron Cross on their uniform, a relic from the Teutonic age which resembled the Christian cross. They also encouraged Christianity in the occupied territories, as the New Testament values of forgiveness, submission to masters, and payment of taxes made the occupied people easier to govern. Joseph Goebbel’s, an anti-Christian radical who followed a mixture of New Age and Eastern beliefs including vegetarianism, keenly proclaimed the Christian message in the occupied territories through his propaganda machine with the slogan “neutrality towards Christ is a dangerous, even impossible thing.”

Perhaps in response to this, Planck adopted an entirely neutral stance to Christianity from then on! In 1938 he had challenged the Indian philosophy that was favoured by prominent members of the Nazi party, criticising its assumption of ultimate meaningless in life, and continued to preach the freedom of will, and the importance of following the calling of an ethical conscience. All of this was a direct contradiction of the message the Nazis pushed. By the end of 1943 the Reich committee recommended that Planck’s public lecturing permissions be terminated. This ended his public engagement with religion.

Planck’s life ended in 1947, two years after the end of the Second World War. It was perhaps a fitting time, for a man who gave much of his life to defending science, principles of conscience, and religious and philosophical ideas from the Nazi regime. He is remembered as one of the few scientists who attempted an all embracing vision of life, encompassing the sciences, philosophy, and religion. The Planck satellite, named in his honour, circumnavigates the Earth’s orbit to this day.

*Quoted in Eggenstein, K. The Prophet Jakob Lorber, 1975.

Above: The Planck satellite in orbit of the Earth.

**********

This article is part of a series. Scientists covered in this series:

Isaac Newton

Charles Darwin

Alfred Wallace

James Clerk Maxwell

Max Planck

Kurt Godel

Albert Einstein

Georges Lemaitre

Jean Piaget

Werner Heisenberg

Erwin Schrodinger

Arthur Eddington

James Jeans

Donald Knuth

Francis Collins