Many people bemoan the death of genuine free parties, but the legal raves and electronic dance music festivals of the twenty first century are not only bigger and better attended than ever; the aim of the original travellers and counter culturalists – bringing attention to political, social and spiritual issues – appears to have been successful. The values of the alternative cultures of the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s have actually been adopted to one extent or another by much more prominent areas of contemporary society.

Festivals and raves have always been areas in which individuals come to discover themselves. They are places where they come to grow. Society itself, arguably, has grown up over the last 30 years, and is more likely to take responsibility for its actions. Environmental issues, animal rights, charity, and alternative spirituality all loom far bigger in public awareness now that in the 1980s. These issues have also been given much more respect by corporations and governments now than in previous decades.

The EDM (“electronic dance music”) scene remains an important influence in shaping and inspiring the values and lives of many who pass through it, and remains a positive transforming influence on mainstream society.

Let’s have a look at the history of free parties, free festivals, rave, etc from the mid-twentieth century to the emergence of the widespread illegal rave scene in the 1980s and 1990s to the proliferation of legal outdoor dance music events since the turn of the 21st century. The term rave has been replaced, but the culture of outdoor dancing is bigger than ever.

The 1940s to 1970s: The rise of free festivals

Festivals of music and other forms of celebration clearly date back to well before the twentieth century and have been common among all people across history. Flutes carved from animal bones and drums made from hide can be traced back to prehistoric times. The use of psychedelic substances for ritual purposes can be traced back several thousand years on every continent. Over two thousand years ago the followers of the cult of the Greek god Dionysius were said to take to the hills around Athens for wild, hedonistic parties involving music, wine, and various other mind altering substances. Dionysius was the god of the wine press, and the god of freedom from worry. He was described as “he who unties.”

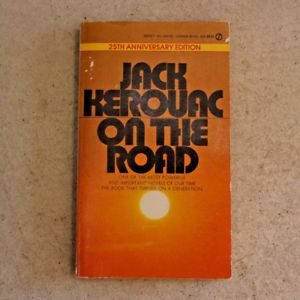

But most musical historians trace “rave” to the beatnik scene of the 1950s and 1960s. Something of a precursor to today’s New Age movement, beatniks derived their views from Buddhist and similar Far Eastern philosophies, but made a very Western interpretation, generally ignoring the disciplinary element of these spiritual paths and interpreting Buddhist freedom and enlightenment as the pursuit of hedonism. The movement was associated with music and poetry. It produced many literary authors including Jack Kerouac and Ken Kesey, popular philosophical authors such as Alan Watts, and the “beat poet” musical genre that inspired Bob Dylan. The “beats,” as they were called, viewed themselves as disconnected from mainstream values. The term “beat” referred to both the word “beaten” – it was ok to be down and out and somewhat disaffected – and to “beatitude” – for they claimed a kind of tragic beauty in their situation and their attempts to use music and poetry to re-establish more important values.

Above: Jack Kerouac’s novels, based around the beatnik lifestyle, became flagship items for that subculture.

Here we already see a common theme to rave and free festival culture. Events are not merely about having a good time: for many who attend they are about experimenting with alternative values, and an alternative form of society. There was an atmosphere of soul searching and anti-materialism which inspired much of 1960s pop music. Beatniks were noted for goatee beards, and for long un-styled hair in both men and women, as a flout of conventional barber’s shop and beauty salon appearances. They often preferred black clothes, and wore items that were unfashionable among the mainstream, such as horn rimmed glasses and beanie hats. They shared ground with the later generations of goths, cyberpunks, and New Agers. There was an emphasis on outdoor parties, drinking, and marijuana use, all done in the spirit of establishing freedom and finding enlightenment.

Something of a continuation, the term “rave up” was used to describe outdoor parties associated with the 1960s psychedelia culture and the early garage and punk rock scene of the 1960s and early 1970s. Psychedelic rock was the forerunner of the Eastern dance music scene which centred around Goa in India. Indian psychedelic rock parties evolved into the Goa trance dance music which lead on to psychedelic trance music in the mid-1990s.

The 1970s brought the first intentionally created free entry festivals, the first of which was Windsor Free Festival. The ethos was to create a mini island of utopia, an example of what society might eventually be like all the time: a free and open society characterized by individuals guiding each other in self-discovery, in an atmosphere of cooperation, fairness, and (eventually) economic self-sufficiency. Other well-known free festivals of the 1970s included the early Glastonbury festivals, the Elephant Fayre festivals, and the Stonehenge Free Festivals.

The 1980s: Police crack downs and the acid house era

The scene exploded in the mid-1980s. Disused industrial buildings became the primary location for free parties. Known as “squat parties,” they were usually held on industrial estates, in disused warehouses in Manchester and then in London and other large cities, in an echo of the original emergence of house and techno music in the warehouses of Chicago, Detroit, and New York. The music of choice was initially acid house, with techno, and then trance adopted later. As the police began to crack down on these squat parties, organisers increasingly looked for secluded outdoor locations, protected by woods, and away from the general public. It was at this point that the squat parties intersected with what was left of the 1970s free festival scene. Many New Age travellers actually lived in inner city squats during the colder months. The travellers found much common ground with the early ravers, they were united by the quest for growth and the celebration of freedom.

The equipment used at free parties, known as the sound system or the “rig,” increasingly became owned by “tribes” of New Age travellers who transported equipment from one location to another in caravan-like convoys of vans and small lorries. New Age travellers were sometimes from gypsy backgrounds, but were often previous urban dwellers who had changed direction in life. A good deal of their ideology had come from the East, many of the older ones had travelled the “hippy trails” and picked up ideas about enlightenment and liberation in India, Nepal, and Thailand.

Their ethos was dominated by a rejection of conservativism and often of capitalism altogether. Capitalism was (and is) seen by New Age travellers as having failed to deal with social problems and entered a terminal decline. They attempted to create an alternative society which they believed would become the society of the future.

New Age travellers were not understood by established 1980s society. They were viewed with a mixture of ignorance and fear and assumed to be dangerous. As incredible as it now seems, by the mid-1980s, Margaret Thatcher really did appear to have convinced herself that they were armed anarchist-communist cells who posed a genuine threat to national security! . A minority of them engaged in genuinely antisocial behaviour: these were generally later additions from the punk community who did not have the same peaceful ideology. But the majority of them were peaceful.

Police violence against New Age travellers had been occurring since the 1970s. But the worst event was to occur in 1985 to a group of travellers known as The Peace Convoy. The group were attempting to travel to the site of the Stonehenge Free Festival, an annual event held in celebration of the Summer solstice. The solstice celebration at Stonehenge had been banned by the conservative government from taking place that year, amidst a growing atmosphere of moral panic at New Age traveller activities.

In reality, most New Age travellers were not followers of the druid religion that focused around Stonehenge. Many were neo-Pagans of one kind or another, others were Christians, Buddhists or atheists: the solstice event was important because of its symbolism for the movement, rather than having a specifically religious focus.

The Conservative ban cited such things as damage to the site, drug use, failure to pay tax on wares sold, and bathing naked. There was a strong feeling among the New Age traveller community that, although almost no one had anything like violent revolution in mind, their alternative way of life had become too popular and too successful and would present a genuine threat to capitalism if it continued to grow. Attendance at the Stonehenge Free festival was doubling every year and the festival had become a month long gathering.

What was to unfold occurred in the aftermath of the so called “battle of Orgreave,” a key event of the 1984-85 miners’ strike. A planned operations based on the highly controversial tactics used at Orgreave was put into place to tackle travellers attempting to reach Stonehenge. A full 1300 police in riot gear were sent to deal with the peace convoy.

The events which followed became known as the “battle of the bean field.” By all accounts of the travellers and of the small number of journalists who witnessed it, there was no battle to speak of, merely a mass assault by police on unarmed civilians who offered little more than passive resistance and non-cooperation, and then attempted, in vain, to defend themselves. Offences were committed by a small number of travellers, but the mass consensus of opinion is that what violence there was from travellers was merely retaliation or defence.

As the Peace Convoy approached the site it was stopped at a police road block. There is no way of definitely determining what happened next. Police claimed that the leading traveller vehicles had attempted to breach the road block. Travellers claim the police simply attacked. The fact that at the crucial time, both the video tape of the police camera blacks out (it is claimed to have temporarily “broken”) and the tapes containing the radio commands were “being changed” (a process that should not have taken several minutes) does not place confidence in the police version of events.

Either way, police with badge numbers covered began to smash windscreens with batons. When travellers tried to escape into a nearby field, some on foot some in their vehicles, they were surrounded by police in riot gear who demanded they hand themselves over. After a long standoff police charged the field in riot gear, smashing into cars and mobile homes to eject people, striking travellers with batons, and in some cases setting fire to their homes.

Kim Sabido, one of the few journalists who had been present, described it as "some of the most brutal police treatment of people" he had witnessed in his career as a journalist. He described people "clubbed" by police, including people "holding babies in their arms." Sabido also stated that much of the footage he took, including the worst incidents, were deleted from ITN libraries before he could access them a week later.

Even the Earl of Cardigan, a Conservative who had been travelling behind the convoy at the time, attested to pregnant women being “repeatedly clubbed on the head,” and that police officers smashed up vehicles with hammers. He maintained these claims under oath six years later, despite vilification from the Conservative establishment and the press, and was key in establishing the use of excessive force by police and securing damages for over twenty travellers.

The police claimed that they had gained intelligence that travellers would be in possession of petrol bombs, a story that quickly unravelled. The police brutality and subsequent media cover up, led by the BBC, was exposed in a 1991 documentary.

Above: A BBC documentary on the events surrounding the Peace Convoy.

Another group of travellers of the late 1980s were to eventually become known as the Spiral Tribe. By the time they took on the name the acid house scene had already seen considerable commercialization and begun to be dominated by commercial marketers and promoters. Police crack downs on gatherings, and the fear of further police violence, pushed illegal raves further underground. This resulted in the commercialisation of the rave ethos, and legal, ticketed dance events began to replace the old free events. Spiral Tribe were a reaction against this and an attempt to lead rave back to its non-commercial roots.

Spiral Tribe members were read in the theories of Robert Anton Wilson and Terrence McKenna, and expected a revolution in human consciousness and society mediated by cosmic forces, and the imminent outbreak of a new age. A general expectation of a new age characterized by a mixing of generally pagan spirituality, environmentally aware green living meshed with today’s technology, a breakdown of government, and a new world characterised by peace, respect, and unity across racial and other divides is a common theme and expectation of New Age thinkers today. It is still a central theme (a marketing theme some would say) on the websites for events like Electric Daisy Carnival.

Others would argue that the increasing awareness of environmental issues, and the increasing responsibility taken by governments towards the environment, the begins of an awareness of “fair trade” by corporations, along with the general diffusion of spiritual ideas into society and the rising popularity of yoga, meditation, tai chi, and the renewal of interest in astrology, signifies a victory for the New Age movement. Such people would argue that New Age ideas have become mainstream not because they have been diluted – but because the insights of the original travellers have been adopted, to a one extent or another, by mainstream society. (Or at least that this process is beginning and has seen significant progress since the raves of the late 80s. )

Left: The spiral tribe logo. Right: Terrence McKenna (photo by Jon Hanna), an icon of the New Age movement, whose ideas were popular among members of Spiral Tribe and their followers.

Many New Age travellers still live the life style in the UK, and similar movements exist in North America and Europe. New Zealand is currently seeing a revival in the New Age traveller lifestyle. Others have abandoned the lifestyle, but kept the ethos going in other ways, sometimes starting green, or fair trade-based businesses.

As well as travellers, the early rave scene had another source of members from a very different area of life: football supporters, and often football hooligans, who discovered rave (and ecstasy) as a natural extension of drinking around the Manchester area after matches. Some claim that the majority of those at the early acid house squat parties were football fans, and the movement appears to have had a positive effect on football hooliganism. The comments of Mike Knowler, a Liverpool DJ at the State nightclub in the 80s and 90s: “We used to have a lot of football hooligans at the State in the 80s. They would cause trouble and start the odd fight. But when acid house came in it just calmed things down. Ecstasy was the love drug in that it just made you happy.”

The theory also exists among academics that it was acid house, more than anything else, that was responsible for ending the era of rampant football hooliganism of the 1980s – disillusioned youths previously drawn to violence instead took to raving, found a very different form of rush and release, and embraced an entirely different set of values.

The 1990s: The mass rave movement

Rave and festival culture became increasingly commercialised across the 1990s. This had a dual effect: it removed many of the political and spiritual ideals, but also spread the ideals that remained to a much larger audience.

The commercialisation of the rave movement was often strongly frowned upon by those who remembered the early scene, or who have stuck with the genuinely “free” version of raves that originated in the UK in the 80s. The organisers of these events have usually read anarchistic books and subscribe to their principles. They are often knowledgeable about anarchistic philosophers.

Anarchy itself does not refer to chaos and to disordered behaviour as it is commonly perceived, but refers to a hypothetical society in which everyone is left to choose, and be responsible for, their own actions without government and therefore without laws. Many of these people achieved a good deal of personal peace and were/are admirable individuals. Others appeared destabilised by the scene or were attracted to it for unstable reasons in the first place.

The 1992 rave at Castlemorton Common is hailed as the last of the free raves. It is the largest free party in UK history: a massive event spanning a weekend and continuing through the next week which attracted at least 25,000 people. It was the largest gathering since the end of the Stonehenge festivals.

Spiral Tribe, who were introduced in the previous section, were directed away from their initial destination – Avon Free Festival – an annual gathering near Bristol. Reportedly, police had dug trenches around the site to prevent entry. Several large groups of travellers had been denied access to other sites in the preceding week, turned away by closed roads or blocked gateways to field entrances, and gathered in laybys and other sites in the area, before eventually converging on Castlemorton Common a few miles away. They were joined by rigs from ten other “tribes,” all of whom set up stages. The music was acid house, techno, hardcore, and drum and bass.

Travellers arrived with their stalls and a mini economy of food, clothes and other traveller wares as well as the usual rave paraphernalia developed. Rings of camp fires marked travellers villages that formed in growing circles around the centre. TV crews from all major news stations arrived and covered the event, which was the lead story on BBC news on both the Friday and Saturday night. The crowd was a mixture of New Age travellers, gypsies, and urban dwelling rave enthusiasts from across the country.

A leader of the community joined in a discussion with two BBC panellists via a live video link from the site and extolled the virtues of the traveller life style, assuring viewers that the site would be thoroughly cleaned afterwards, and that anyone causing problems with locals would be “dealt with” without any need for police involvement.

The tabloids had a field day from the beginning, reporting children injecting heroin in cars, travellers dogs slaughtering sheep, garden fences ripped off for use as fire wood, and farmers patrolling the boundaries of their land with shot guns. All of these claims had at least some truth to them, but they did not represent the actions of the majority. A small number of individuals also appeared to have arrived from towns, with the sole aim of causing trouble with either police or travellers.

Above: The five news reports from the BBC's 9PM news braodcast on the Castlemorton Common gathering, which ran coverage as the lead story on both Friday and Saturday nights.

The gathering was far too large to break up using force. Eventually the police simply staved it to an end by letting no one re-enter the site. As food and other “supplies” ran low things ground to a halt a week later. Thirteen members of Spiral Tribe were arrested afterwards, appearing in court wearing T-shirts displaying the logo “make some noise,” but were cleared of all charges.

Castlemorton marked the end of the mass free party movement. Legislation was quickly passed which was to form part of the Criminal Justice and Public Order Act (1994). The duty imposed on local councils to provide sites to accommodate travellers was repealed. Outdoor gatherings with music “wholly or predominantly characterised by the emission of a succession of repetitive beats” were made illegal.

But the dancing did not stop. The free party scene was quickly replaced by legal, licensed, commercial raves organised by profit making entertainment companies. The most notorious were Sunrise, a company putting on live outdoor dance events which avoided police regulation by pitching their raves as members-only club events that the police could not close. Tony Colston-Hayter, founder of Sunrise and the so called “Mr Big” of illegal rave, once commented that “Maggie should be proud of us” in an ironic reference to the British Prime Minister and their venture as a form of enterprise capitalism. A former Young Conservative, Sunrise’s PR rep Paul Staines was noted for spending thousands on champagne breakfasts at hotels, and described his political views as “Thatcher on drugs.” Staines reinvented himself as a liberal blogger in the early 2000s. Colston-Hayter made the headlines once more in 2013 when he was convicted of stealing £1.3 million from Barclays bank, and an additional £1 million in credit card fraud when boxes of stolen credit cards found at his flat left a trail of purchases of luxury goods.

The 90s were also noted for ever increasing antipathy to the new drug of choice, ecstasy. The feeling at the time among ravers, which was born out by the statistics, was that the media were happy to ignore the undoubted and well established dangers of the favourite mind altering substances of their general readership—alcohol and cigarettes—while demonizing the statistically far less dangerous counter cultural preferences. (A recent study by the Federal Centres for Disease Control and Prevention found that 6 deaths are caused by single episodes of binge drinking alcohol every day in the United States, in comparison to the handful of ecstasy related deaths from around the world each year.)

The most high profile of the ecstasy related deaths of the 1990s was that of Lear Betts, and even here all was not what it seemed. The sensationalised media claims that her death was her first use of the drug turned out to be false, and a media prompted £300,000 investigation involving 35 officers to find the source of the ecstasy pills revealed no further names than the four friends who had been at her house that evening. More cynically, the anti-drug poster campaign that bore her image and was positioned in 9000 prominent locations around the county, which was widely reported as a pro bono endeavour of compassion and concern, was created by three companies who all turned out to be connected to either Lowenbrau brewery or to Red Bull, at a time in which breweries were widely known to consider ecstasy to be a major threat to profits, and when the Red Bull was seen as an alternative to ecstasy for clubbers wanting more dance stamina.

Regardless of the genuine dangers of drug use, most people don’t realise that the anti-drug campaigns of the 1990s were paid for by breweries, whose profits had taken a downturn...

While unquestionably hazardous to mental and physical health on occasion, and while I cannot personally be said to condone them as they are only a substitute for real bliss and real spiritual experience, the ecstasy pills at the core of rave culture were probably a preferable alternative to everything that alcohol culture continues to produce on high streets on a weekly basis.

Arguably the commercialised raves of the 1990s, and to an even larger extent the still more commercialised and still more regulated and sanitized rave-styled dance music festivals of the twenty-first century, were more wholesome. Not only did the legal aspect ensure better safety but also encouraged a more balanced life style. Typical people at events like Electric Daisy Carnival are university students or people who work regular jobs, and not people who lived exclusively for the dance music lifestyle. It is a balance that is probably healthier and preferable, overall.

From approximately the mid-1990s to the years around the millennium rave lost ground to indoor clubbing. Ministry of Sound in London, Cream near Liverpool, and Gatecrasher in Sheffield issued in a new era of “superclub” – clubs which opened through the night with capacities of several thousand. The other major development of the 1990s was the explosion of interest in the Balearic music scene. Ibiza became the hedonistic holiday destination of choice for tens of thousands each year. The focus was on progressive house music which had replaced acid house, and increasingly on trance music which shared equal playlist space with progressive house by the late 1990s.

The 2000s and 2010s: Rave becomes EDM

The 2000s and 2010s have seen dance music grow to an unparalleled level of popularity and mainstream attention. Despite this, there have been few if any genuinely new forms of dance music appear in the twenty first century that have made a large and lasting impression. There have been many minor innovations, but they have not achieved worldwide success, and have usually been short lived regional scenes.

The 2000s began with a movement from dance music to guitar music, as the superclub culture that had gripped the UK around the turn of the millennium began to unwind. But it was not to last for long. Commercialised raves have returned on a mass scale over the last 10 years. Both free raves and legal ticketed raves are larger than ever. More and more people are being drawn in, a large number of them students and white collar workers in their twenties.

Organisers claim that an alternative to the aggression of high street alcohol culture is what attracts them. But the old dream of entering an ideal world of freedom and respect, a little island of refuge away from the values and behaviours of the larger world in which alternative values can be experimented with, is still keenly expressed. And the wider world itself has become a little more like that ideal.

The electronic dance music sections of music festivals have grown across the world. They draw crowds larger than the largest raves of the 1990s. Specialist dance music festivals are also proliferating. This time the USA has lead the way. The entire movement has exploded on a simply unparalleled scale – far vaster, this time, than any of the previous incursions that rave has made into the mainstream.

Rave in the twenty first century has succeeded, and succeeded for very twenty first century values. It has succeeded because it has mastered organization, bureaucracy, safety, and the projection of public image. The new raves make no attempt to hide. They occur in very public and very mainstream places like sports stadiums. There is an overt effort to break away from the old school days, to the extent that traditional rave paraphernalia are often banned! Some venues, such as California’s Hard Summer festival, have explicitly banned such items as fluffy boots, gas masks, bubble gum, furry toys, glow sticks and many other accessories of the 90s “candy raver,” which are confiscated on entrance. A clean break is sought from anything associated with the “Crasherkids” of the 1990s UK clubbing scene.

Ultra Music Festival, originating in Miami in 1999, now runs across three days and has an attendance of 300,000. The US dance event Sensation has spread from the US and has now held events in seven countries. The Global Gathering brand grew out of the Godskitchen house and trance clubbing night of the UK in the late 90s, and held its first outdoor event in 2001 at Long Marston airfield in Warwickshire. It has since been held in several countries. Tomorrowworld began in Belgium in 2005. The 2017 Belgium event was split over two weekends with a combined attendance of 400,000, and sister festivals were held around the world.

The UK continues to be a worldwide dance music centre. Festivals such as Creamfields, product of the 1990s house and trance nightclub Cream, draw huge crowds each year. Glastonbury, the world’s best known festival, has grown from an attendance of 1500 in 1970 to 170,000 in 2017, with attention shared between guitar and music and electronic dance music. Glastonbury remains the world’s largest green field festival, and retains ties to its New Age traveller heritage, retaining the Healing Fields and Green Fields spaces. Glastonbury was also the original venue of the Glade festival, for many years the UK’s largest psytrance festival, which originated as a free party offset from the main Glastonbury site.

Above: The super-sanitised face of rave in the twenty first century. Electric Daisy Carnival’s 2019 promotional video.

The best known contemporary dance event is perhaps Electric Daisy Carnival, a spiritually themed event with a website that draws on pagan and New Age ideas emphasizing the meshing of ancient wisdom and the technology of the future, self-discovery, and unity with others. Other than that, there is perhaps only a superficial resemblance with the 80s free parties. Free Wi-Fi and ATMs are available onsite, along with huge Ferris wheels and other rides. Arriving at the site by private helicopters can be arranged through the website at a cost of $3000 one way or $5500 for a round trip. These are but a very small selection of an enormously popular and growing outdoor dance music scene.

Dubstep is arguably the only genuine originality of twenty first century dance music. Recombination of old sounds is the new innovation.

Music itself has progressed relatively little in the twenty first century. Dubstep is arguably the only genuine innovation. Genre’s of electro house, tech house, tech trance, Dutch house, Swedish house, and even the “poppy” tropical house sound that dominates in high street nightclubs are more combinations of several previous sounds than anything definitively new. The fact that there has been no new musical technology, just improvements to what already exists, is partly responsible.

One thing that is noticeable is that the rebellion has gone. The driving early 90s techno sound that was synonymous the counterculture and UK anarchy has fallen away. The face of the EDM today is not rebellious. It is about balance and harmony, even conformity.

The movement away from the old production model to independent artists recording their own music and releasing it on YouTube and Beatport has meant that music has been heard that would never have previously got an audience.

There have been many regional innovations. Trap music had found some mainstream success in the USA in the early 2000s, but didn’t really take the listener anywhere that hip hop hadn’t done. Trap was basically hip hop with EDM sounds. The UK has offered many variations around garage, including Bassline in the Midlands, which produced some well-known chart tracks, but failed to catch on as a worldwide movement, and quickly slipped out of the UK limelight.

Two genuine wonders were produced, originating in Chicago and in the UK’s Lancashire respectively: footwork and donk. Footwork, in another universe, might have revolutionised both the sound and the look of dancers in a similar way that trance had, but despite viral videos of the extraordinary dance style, it failed to make a lasting impression outside of Chicago. Donk became something of a sensation in the “badlands” of Northern England but was viewed with a mix of humour and amazement everywhere else. It involved a short stabbing bassline that sounded a bit like a series of “donks,” and rap lyrics about being arrested and other typical “hood” themes performed in thick northern accents.

Above: A Chicago Footwork “battle” between two neighbourhoods

Above: Jaimie Hodgson’s entertaining documentary about the “donk” music scene in the North of England.

Funky emerged in London, sharing roots with Grime and Jungle, but failed to spread. There was a strong British African influence, a much happier and more light hearted sound and atmosphere than most MCed music. A large number of regional scenes emerged around the world that were collectively termed Ghettotech, sometimes originating in Brazil, Central America, Western and Southern Africa, and found a following in immigrant communities from these locations around the world.

Dubstep alone is arguably the only real innovation of twenty first century dance music that has made a worldwide and lasting impact, and even this collapsed into brostep, which was just another way of recombining older sounds. The EDM that dominates is a really a combination of all previous sounds in dance music.

The 2000s were noted for three developments in the drug scene. The first was that ravers got sick of low quality ecstasy pills. Suddenly everyone wanted MDMA which, initially at least, was less likely to be diluted with impure fillers. The second was the explosion in popularity of psychedelic mushrooms, which became widely available in shops across the UK and stalls at festivals, as a loop hole in the law surfaced which allowed for the sale of fresh unprocessed magic mushrooms, but not for items which had been prepared (for example through drying). The British summer of 2004 was pronounced the third Summer of love by NME magazine, after the acid fuelled first summer of love in 1967, and the ecstasy fuelled second summer of love in 1988. Crowds of people on mushrooms flooded public areas, not only at festivals but in parks and even high streets in many UK towns and cities.

Another addition was the sudden widespread retail of salvia divinorum, a South American plant extract which renders extremely powerful psychedelic effects. Salvia had been available to buy in UK shops selling smoking paraphernalia for years, and there was brief surge in its use around 2004-2005. But it was simply too strong to attract many repeat users, and was eventually banned in 2016.

The third development was the spread of “legal highs” – manufactured, synthetic products that were designed to mimic the effects of drugs but which were made from legal chemical formulae. Veiled as plant food or cleaning products, and always stressing “not for consumption” on the packaging, but with names and graphic design that were highly in-keeping with clubbing and cannabis culture, they lead to a game of legal cat and mouse as the government banned legal highs as they became popular, only for spin-offs to emerge a month later with slightly different chemical formulae and almost identical effects.

Above: A selection of popular intoxicants, both legal and otherwise.

Legal highs were actually nothing new. But their effects had previously been generally disappointing, either not producing much noticeable effect, or producing unpleasant effects. This began to change around 2004-2005, and reached its pinnacle with the emergence of Mcat a decade later, which was so effective it was viewed by many clubbers as preferable to the wave of low quality ecstasy and cocaine that was hitting the UK at the time. Finally Black Mamba and Spice appeared, muscle relaxants with somewhat psychedelic properties, that created a zombie-like effect in users which was jumped on by the tabloid press. The effect of the latter two was highly unpredictable and apparently more dangerous than any of the traditional recreational substances, and they were implicated in a spate of violent incidents, breakdowns, suicides, medical emergencies and deaths in prisons and among the public in 2015 and 2016. The supply of all of the substances mentioned was eventually banned, but there is a continuing demand, and continuing supply of them, as illegal street drugs.

Genuine free parties – parties with no entrance fee – continue, and they are still disrupted by the police. Technical innovations, especially the internet, and global positioning software on phones, has made it easier to stage events without police knowledge. But the increasing popularity of rave was not met with approval from all sections of the rave community. The organisers of the Czech Tech free gathering that had been organising parties across the Czech Republic since 1994 stopped putting on free music events in 2006 despite ever-growing success. Their more recent gatherings had attracted up to 40,000 people. The growing popularity actually seemed to be the problem. They stated the reasons for discontinuing as (i) a gradual abolition of the ideology of free techno parties (ii) parasitic behaviour of those with no real interest in techno or its ethos, (iii) lack of ability of attendees to show basic respect for others in the free party space.

Some of the ethos may have been lost from the early days, but enough of it has been maintained, I would argue, and more significantly the values of the New Age travellers of the 1980s have diffused into wider society to some extent any way. The expectations of the beatniks and hippies, and the travellers and New Agers of the late twentieth century, that a cultural transformation was coming, do not appear to have been so far off the mark.

There has been no radical and sudden transformation. Instead there has been a gradual increase in awareness of several issues from environmentalism, to animals rights, to alternative health, to anti-materialistic, alternative spirituality, that were important to those involved with the movement, and which their parties, the police involvement, and subsequent media attention, were influential in bringing more clearly into the public eye. That these values that were once rare have become almost mainstream is a testament to a success story.

Spiral Tribe, we recall, appeared in court wearing t-shirts emblazoned with the words “make some noise.” Rave has been responsible for getting people to listen more attentively to many ideas and causes as well as to music.